Apple recently announced that they will be releasing a new “Sources” tab in iTunes Connect. iTunes will now track the referring url and an optional campaign ID, passed in as a url param. This is a huge improvement, and it will work great for developers that build exclusively on iOS.

The problem is, iOS doesn’t dominate the market anymore. Most developers need to build for both iOS and Android. If you’re building on both platforms, having your data in an iTunes silo is hugely problematic. We’re going to explore how attribution works, why it’s a problem on iOS and what apple could do to solve it (hint: Android has already done it).

The problem with mobile attribution

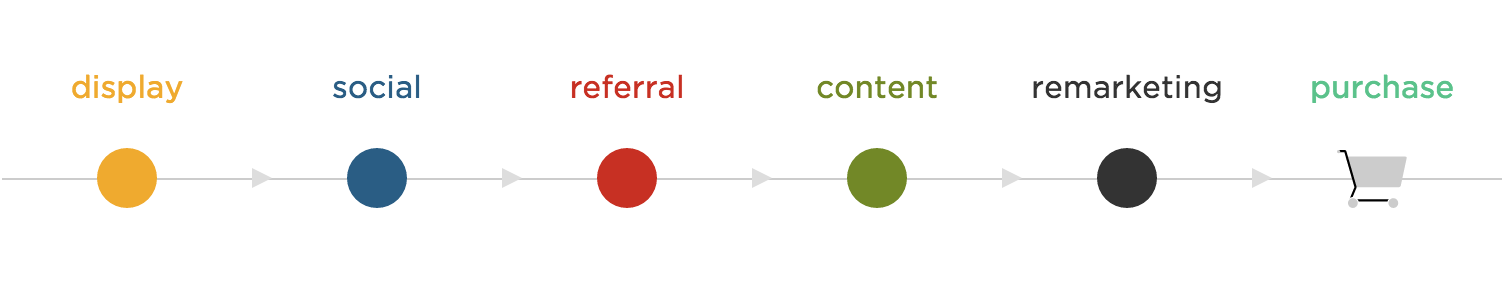

If you sell things on a website, there are excellent ways to see what you’ve gained for all that effort you put into marketing. You can easily see where people came from. The web has HTTP referrers built right into the protocol, and in the cases where that doesn’t work you can use UTM tags or campaign-specific landing pages.

Knowing what works is critical. Even if you’ve built something people want, you still need to get their attention and show them what you’ve built. When resources are limited, dumping what little you have into the wrong channel or the wrong campaign can have real consequences. Knowing matters.

When you put something on an app store, you don’t have any say over the tracking data they give you. You don’t get to see where people came from or what params were appended to the url. It’s very difficult to know where you should spend the limited resources you have. Until recently, this was the plight of every app developer publishing to an app store.

How it works with Android and Google Play

Google has come up with a simple, open solution to this problem. They pass the params from the app store URL into the app when it is first launched. Developers can now see where their customers came from. It’s a simple solution that takes advantage of best practices on the web. It works for every ad platform, it doesn’t compromise our privacy, and it works for every use case we can imagine.

Apple’s closed garden approach

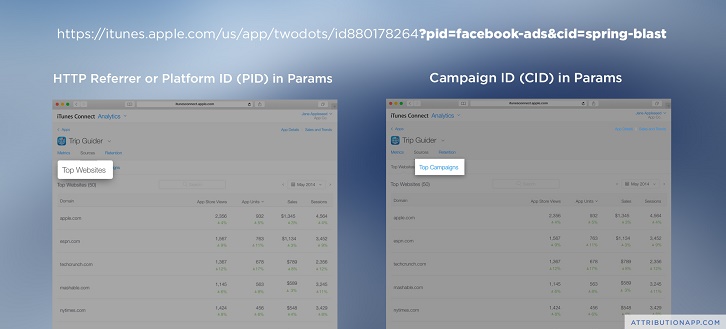

Apple’s solution looks similar on the surface, with one important exception. Apple passes the params to their own tracking system but doesn’t make them available to the developer. Let’s take a look at how it works:

https://itunes.apple.com/us/app/twodots/id880178264?pid=facebook-ads&cid=spring-blast

This is a great start but without the raw params, developers can’t see where actual users came from. Without the ability to tie the data together, developers cannot do a few really critical things. Let’s explore what those things are and why they are important.

Advantage to passing params: Deferred Deep Links

Here’s a scenario: you’re browsing Amazon.com on an iPhone looking at a fancy new coffee grinder. A message pops up, letting you know that Amazon has an app. You download the app, open the app, and get dumped into a blank slate. There is no reference to coffee grinders. “That’s foolish,” you say “shouldn’t Amazon know I was looking at porlex coffee grinders?”

Amazon doesn’t know because there is no (supported) way for developers to pass data through the App Store. If we could append params to the App Store links and load those params at app launch, we could simply pass through the porlex grinder product ID and load it when the app was first launched. Apple has done a great deal to support deep linking, but they’ve ignored the critically important first link.

Advantage to passing params: Discount links and app sales

Here’s another scenario: you have a successful company, and you’re launching an iOS app with in-app purchases. You want to offer a discount to you mailing list. Maybe you want to give them 50% off in app purchases. Great idea, but it’s not possible. There’s no (supported) way to identify which users came from your email blast on iOS.

Advantage to passing params: See ROI across devices

Let’s looks at a common scenario for people who sell the same app across multiple app stores. Maybe you sell a productivity app on iOS and Android. You’re in the middle of a Christmas promotion and you want to see how your campaign is doing on Twitter versus Facebook. There’s no way to merge the data, the iTunes half is locked in a silo.

iOS Attribution Approaches

As engineers, having a problem means we build a solution. The solution, in this case, is for ad networks to fingerprint every device that clicks an ad. This can be done using the Apple-regulated IDFA (ID For Avertisers) or by fingerprinting the device using a combination of browser information and the IP address.

Attribution Method: Using the ID For Advertisers (IFDA)

When you click an app ad on Facebook, your unique IDFA is stored on Facebook’s servers along with a reference to which ad was clicked. You include the Facebook SDK in your app so that your app can send Facebook the IDFA of every user that opens your app. When Facebook sees a match, they will respond with “yes, we sent them.” This is a very reliable method, because it’s based on a unique ID that rarely ever changes.

Limited platforms caveat: Because IDFA’s require an integration with each advertising platform, it is unlikely that you will find an SDK that is integrated with industry specific ad platforms, affiliate sites, or any custom ad deals you’ve made.

Waste caveat: Identifying users by IDFA requires requires an unruly amount of code. There are SDK’s on top of other SDK’s and any app advertising on more than one platform ends up with megabytes of unnecessary code. Spread across hundreds of apps on millions of phones, this adds up to colossal waste. A phone’s storage space should be reserved for music, photos, and code that provides value.

Privacy caveat: IDFA’s should not need to exist. This is a unique identifier – specific to your iPhone – that is the same across every app. This ID is passed around an entire ecosystem of analytics providers, ad networks, and individual apps. In many cases is is saved along with geographic information, photos, and other personal information. Unique ID’s don’t exist on desktops and they shouldn’t need to exist on phones. If we passed the params through the app store we could get rid of IDFA’s. That’s a huge win for privacy.

Attribution Method: Fingerprinted Redirect with URL Parameters

Tracking with UTM params is great. What if we could somehow pass an arbitrary list of params from the app store into our app? Well, you can. It’s just not as reliable. The way to do this is to set up a link redirect service, similar to bit.ly. Every time you link to the app store, it goes through this redirect service. When a request hits the redirect service, it stores the IP address of the request along with the user agent making the request and any other identifying information available. That information is used to create a semi-unique device fingerprint.

If the user downloads the app, that same fingerprint data is sent from the app on first launch. If a match is found, the params from the app store listing are passed back into the app, along with the referring URL. This can be used to identify anything you want to track about the source – including discount codes, affiliate markers, and cross-platform campaign names. This concept is further explained in Implementing Deferred Deep Linking on the URX blog and it has been productized by Tapstream. We’re working on a similar methodology at Attribution that we hope Apple will make obsolete.

Reliability caveat: Fingerprinting can break down if many people in the same place download an app at once. Imagine launching an iOS app at SXSW. When a throng of people with the same iPhone, running the same iOS, all download the app from the same cell towers, there’s no way to tell them apart. Compared to desktop computers, iPhones are less unique and hence they are harder to fingerprint. In most cases this is not problematic but it can break down at conferences and events.

There’s also a speed/accuracy tradeoff. Additional fingerprinting information is available via javascript, but loading an actual page and executing javascript code may noticeably slow the re-direct. Nobody wants that.

Apple: just pass us the params

All of this would just go away if Apple passed the params from App Store url’s into apps. No more privacy issues, no more heavy SDKs, and no more developers pulling their hair out. As a bonus, app developers would have the ability to privide a much better first launch experiences with deferred deep links. Everybody wins.

We can’t think of any reason why Apple would choose not to pass the params. Maybe an oversight, or maybe a conscious decision. Either way, we hope they change it.

Apple, please, Just pass the params.